Tumarkin before Tumarkin: 31 early sculptures | תומרקין שלפני תומרקין: 31 פסלים מוקדמים 22/05/2014 - 11/06/2014

Tumarkin before Tumarkin : 31 early works

Gideon Ofrat

This was the moment before the polyester relief assemblages that Tumarkin would exhibit at “Bezalel” after returning from Paris in 1961. This was the moment before his material abstractions after Antonio Tapias and Alberto Burri. This was the moment of ‘nature’ that preceded the ‘cultural’ explosion (science, history, technology, ethos, war) in his works, and after the long months of involvement with the Berthold Brecht sector. This was also before Tumarkin’s politico-critical works. But above all, this was the moment of establishment of the artist’s sculptural maturity, the defining moment when he emerged as the sculptor of his generation in Israeli art.

August 1954: Yigal Tumarkin, aged 21, recently discharged from his military service, comes to Ein Hod to learn from Rudi Lehman, and finds the outsize master breathing over his wooden animal carvings. Tumarkin shows the 51 year old German-Israeli sculptor some wood-carvings of fishing and the sea that he has brought with him: and then, one day, Rudi said to me “Why don’t you make small animals?”, and I say “Yes, we could have a competition – who can make the smallest donkey” - “Everyone has to make his own ‘Adam and Eve’” Lehman (who had carved Adam and Eve in wood in 1939) would later tell his student, who would also create Adam and Eve (in welded iron) in 1957, preferring to concentrate on Adam, and not exactly in the Garden of Eden…

For more than a year Tumarkin carved little wooden animals, dividing his admiration between the Italian sculptor Mario Marini (known chiefly for his sculptures featuring horse and rider) and the French sculptor of animals Pompon. Even when he moved from wood to iron in 1956-57, he continued to make small creatures – “cat” and “owl” – the stars of Rudi Lehman’s wooden menagerie. The rules of geometric volume learned from his teacher would travel with him all the way.

However, in 1956 Tumarkin decided to go to East Berlin, to work in the Berliner Ensemble Theatre. This was when he began working in iron: I decided, with the kind permission of Brecht, to create iron sculptures at the theatre, to use the theatre’s workshop. But the works themselves were actually begun during a visit to Israel: Tel Aviv, end of summer, 1956. Inspired by Yitshak Danziger, I am making my first iron sculpture – two owls sitting one on the other, symbol of Athena, goddess of wisdom and the ‘Medura’ (Bonfire) Club where the bohemia of Tel Aviv meets. These were the critical months in which Israeli sculpture reached the summit of abstraction, in particular turning from wood and stone to the medium of welded iron. The initiators of this change were Danziger (who had returned from London in 1955) and Yehiel Shemi, both of them members of the “New Horizons” Group. The English abstract sculptors (Lynn Chadwick, Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler et al.) were the landmarks, inspiring Shemi to create bird sculptures, nests and all, from welded iron sheet, most of which reveal the internal spaces and/or the skeleton, with iron rods embedded in the head. Danziger’s sculptures are more constructivist and flatter, but still have a lifelike semblance due to their sharp “legs” (the outcome of Danziger’s focus on drawing and sculpting animals 1945-1950). One way or another, welded iron was, at that time, the message of Israel’s avant-garde sculptors, conveyed in 1958 in the group exhibition at Gan Ha’em in Haifa. At the end of the summer of 1956, Tumarkin adopted the message of this medium for his new sculptural expression.

Tumarkin returned to Berlin for a very short period after visiting Israel. After the death of Brecht on August 14th 1956, he left for Amsterdam, where he remained for about a year. Amsterdam, it should be noted, was an important avant-garde centre in Europe at the time. The Stedelijk Musuem, under the directorship of Willem Zandberg , was equipped for and open to American abstraction and Pop-Art (sometimes even to Israeli artists such as Zaritsky, Ardon, Ticho, and Kahane), while the Netherlands group of Cobra artists gathered in Amsterdam, their works conveying aggressive expressionism, bestial and primitive.

In Holland, during the year of 1957, Tumarkin created five designs for various theatrical performances, and began working in iron (and occasionally bronze) in expressionist and primitive styles influenced to a considerable extent by abstraction. He became acquainted with the Cobra artists, and perhaps integrated some of their elemental spontaneity. Most of the works discussed here are from this period and this trend. I left Holland with almost abstract sculpture. Vegetation of some kind. Very expressive … Appel and the Cobra – expressivism par excellence. It’s the same with sculpture.

However, Paris was the city considered as the Mecca of modernism, even when the torch was handed to New York in 1940 when Paris was overrun by the Nazis. Among others, quite a few Israeli artists were living and working in Paris at the time, not least Tumarkin, whose life as an artist was in this city and not in Amsterdam. (Israeli artists would only discover New York in the mid-1960s.) So in 1958, Tumarkin settled in Paris. Initially he lived in Montparnasse, in a room in the atelier of the Hungarian sculptor Szabo. In the courtyard there were piles of scrap metal, including crates and odd nails, which would play an important role in Tumarkin’s oeuvre. This was when he became friendly with César, Giacometti, Germaine Richier, Maryan (formerly Pinchas Burstein of Israel) and others, who used to sit in the Café Coupole on the Boulevard Montparnasse each morning. The primeval and amorphous figures created by the Parisian Jean Dubuffet in 1954 are also worthy of note – small Art-Brut sculptures in various materials, (including cast iron). While César – whose clique also had some influence on Tumarkin – was one of the more important sculptors of the Parisian “New Realism” (the French version of Pop-Art), the other artists belonged to what was known in 1959, as it was at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as the “New Human Imagists”. In Europe and in Israel, they preferred the term “new figurative”. One cannot really relate to the early works of Tumarkin without exploring this issue in depth.

As Pierre Réstany, the leading theoretician of the Paris avant-garde at the time declared: together César and Germaine Richier represented the sculptural summit of the 1950s in Paris. He added: For Germaine Richier, for whom “After 50” was “before 60”, as it was for César, man has become a fleshly object, has become meat-matter …Man and beast living together logically in this organic vision of the flesh. In Richier’s work, the movement, breadth and placement of a woman’s hips turn her into a toad or a grasshopper; the male sometimes resembles a bird or a tree … As for César, the living creature is merely an organic descendant of the meat-matter.

César and Richier – the echoes of their creations during 1957-58 influenced the early sculptures of Tumarkin in no small measure.

The 23 items in the exhibition “The New Human Image” at MOMA included several by the artists referred to so far - Karl Appel, César, Richier, Reg Butler, Dubuffet, Giacometti (as well as Francis Bacon, Willem de Kooning and others). Now a new generation takes the stage after the horrors of WWII, presenting images of mankind afflicted, tormented, debased, wounded, having lost all semblance of humanity. The wind of Existentialism was blowing through these works that condemned mankind to an accursed, godless existence. Man’s inhumanity to man (the death camps, the atomic bomb) was expressed in dehumanized sculptures of injury and abuse of the human body. Peter Salz, curator of the exhibition, wrote:

These images sometimes frighten us in their despair. They were made by artists who have not yet found satisfaction in ‘real form’ or even in the most aggressive acts of artistic expression. Perhaps they embody the mechanical barbarism of an era that, without denying Buchenwald and Hiroshima, is preparing for even greater violence in which the whole earth will be the target. Or perhaps they are expressing their rebellion against a dehumanization in which mankind is apparently reduced to a mere experimental object.

The limbless female torso of welded and “scorched” iron, that César created in 1954; Giacometti’s bronze “figurines”, lean and frail, from the end of the 1960s; remnants of a man made of scrap metal that Paolucci cast in bronze (1`957-58); Germaine Richier’s tattered, mythic bronze figures, slashed, pierced and distorted (early1950s); these and all the rest convey the message of the human condition heard by the new generation of artists worldwide. In Israel, the message imparted by the generation of that decade, a new generation of artists that overran exhibitions around 1958. This was the generation that had not yet digested the lyric abstractions produced by the New Horizons Group, demanding expressive, pessimistic figurative works (slightly surreal) in need of abstraction.

In the background, the ears of Paris were attuned to the words of Jean Paul Sartre: “Hell is now!” (“No Exit”, 1944). The philosophy of the Left Bank, where Tumarkin lived, was drowning in the great existentialist nausea that engulfed the hero of Sartre’s novel “La Nausèe” (1932): “There is no reason to exist … Do you really want to say that life is pointless? That what they call pessimism is nothing?” Sometimes Sartre’s writings can almost be interpreted as if they were paintings or sculptures of the death of Paris in that era: “Essentially it (i.e. the electric chair / G.O.) stays the same with its black velvet, and thousands of tiny red nails hanging in the air, absolutely dead. This enormous belly facing upward, bleeding, swollen – it’s swollen because of the thousands of dead nails; it’s not a bench, it’s a belly floating inside this carriage, under those grey skies. It is not a bench. At the same time, it could be a dead donkey, for example, swollen with water and floating in the stream belly up …”

Furthermore (unlike the “year of Sartre”) it was not in human freedom that Tumarkin of Paris found the root of the evils of existence, but rather in the cruel existence of humanity itself, deracinated and unprotected (what Albert Camus called “the absurd”). However, it can be said that Tumarkin of the mid-1950s had integrated the Parisian spirit of existentialism and translated it into his merciless iron sculptures.

Until recently, we in Israel have only been introduced to some 15 early works in iron from Tumarkin’s Holland-Paris period. Most of them are of creatures – Cat, Owl; myths – Ezekiel’s Vision, Sand-Fowl, Adam and Eve; and some variants of the “Homage to Otto Lilienthal” (the German-Jewish engineer, pioneer of flight in the second half of the 19th century). Some of them were exhibited in August 2011 in “Yigal Tumarkin: Paris 1957-59” at the Hezi Cohen Gallery in Tel Aviv. Characterizing those works was the relatively small size of most of them – 30-50 cms. In addition, there was a conspicuous use of triangular iron shards welded together (Owl, Sand-Fowl) to form spiky “wounded” works (evident in Israeli avant-garde sculpture of that time – see Y. Shemi’s “Mythos” of 1956, or Danziger’s “Burning Bush” of 1959, or the statues of Dov Feigin and David Palumbo from the same year). The works of Tumarkin are highly figurative abstractions, very primitive, two-dimensional, of welded rusty scrap iron. They are pierced as if by fire, dripping with melted iron like wax (“Burning Bush”), joined in some cases with narrow iron strips. Many of them are elevated, either on quasi-animal “legs” (“Adam and Eve”) or by means of “tripods” (“Ezekiel’s Vision”, “Unnatural Birth”). The rents and grooves in all of them – in the tradition of Germaine Richier – allow one to see through or into them, giving the viewer a sense of decomposition. Many of them have wings – of birds, of angels (“Baroque Clock”) or even flight instruments (“Homage to Lilienberg”). Several resemble dried thistles – an image used in the same period in the paintings of Lea Nikel, who was living in Paris, influenced by the “Cobra” artists and even more strongly by the spiky paintings of Wols (Otto Wolfgang Schultz, one of the fathers of Tachism). One senses that young Tumarkin drank from the same source. Additionally, and surprisingly, “Ezekiel’s Vision” and “Sand-Fowl” seem to be full of optimism about resurrection from death and cremation. (With absolutely no direct connection, it should be noted that, circa 1955, such themes in Israeli art integrated nationalist aspects linked to Holocaust and resurrection.)

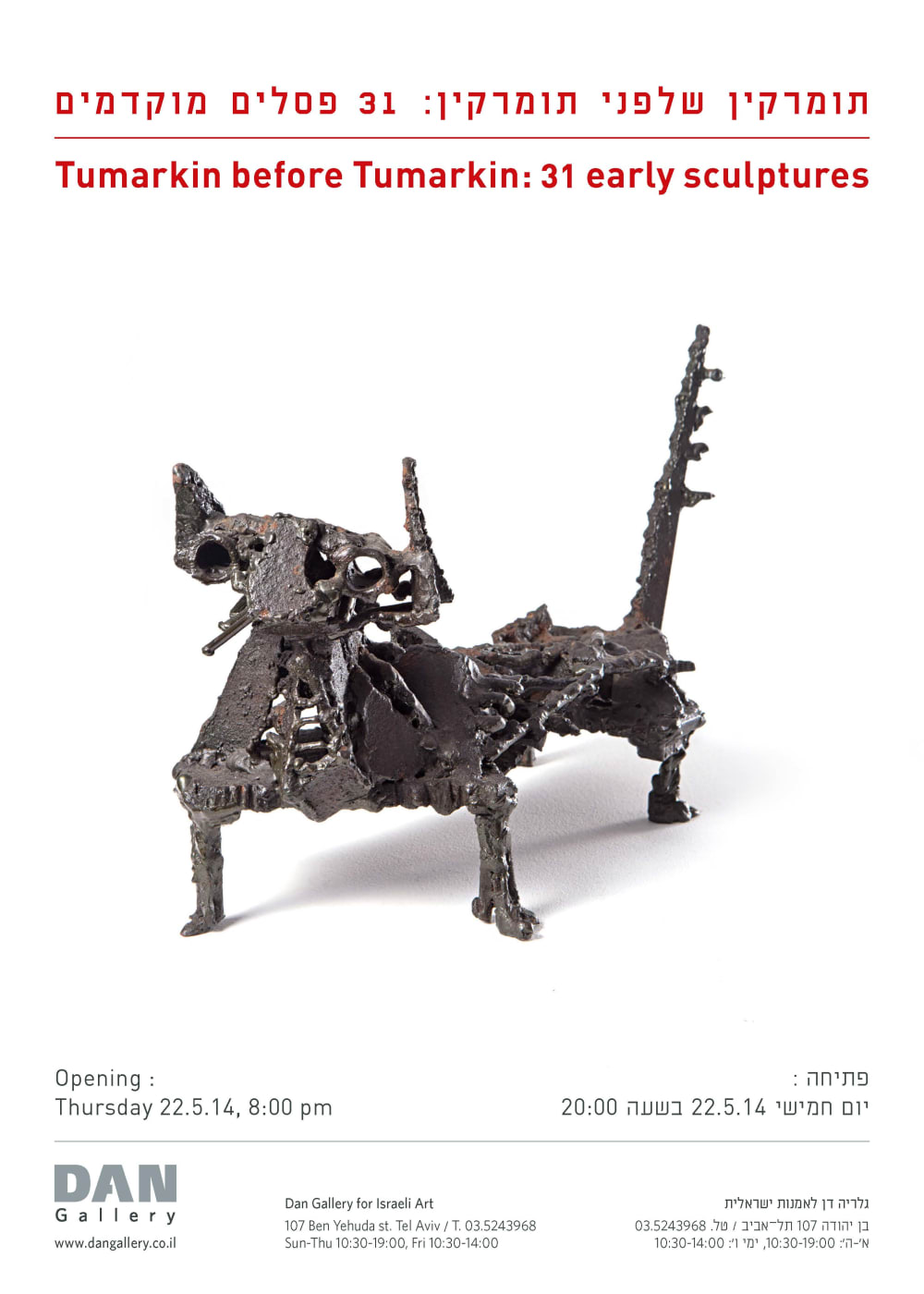

Primed with all these facts, we now turn to looking at Tumarkin’s 31 unfamiliar sculptures, created during 1957-59. The number of small animals among them confirms that Tumarkin still remembered the miniature wooden creatures he carved under the aegis of Rudi Lehman. The lizard, the cat, the reptiles, the bird, the cock, the fish et al. are in the majority, with relative emphasis on marine creatures – memories of his youth on the beach at Bat Yam, activities in the Maritime Association, enlistment in the Navy, and even repairing boats when he lived in Haifa in 1955. However, from every other point of view these are very different works, a revolt against Lehman’s organic charmers. Tumarkin’s works of 1957-58 are characterized by sharp, angular forms penetrating various organs. They are complex welds of ratchet-wheels, iron strips, rods and tubes, discs, nails, bolts etc. They also display the tension between the torn outer face and the exposed interior. They combine surface works (relief welding of organs, or rough, coarse texturing) with careful reliefs composed of triangular iron rods, scaffolding, et al. Thus the works represent prehistoric creatures, inhabitants of a prehistoric space, brutal people, even totems. They blur the dichotomy between man, beast, and vegetation. In this mythical existence, ungoverned by any rationale, life and death also combine. Tearing apart, dissolution and rot are present in all these sculptured creatures, including wounded angels.

Look at the sculpture “Angel,” a figure with an injured wing, beaten, an angelic refugee from disaster, one wing serrated with triangular incisions, the other a skeleton of five thorny iron rods. Three “legs” of bars support the rusting iron on which the angel stands. His legs are pipes; his body is mutilated, and the coxcomb of his head is like tongues of flame. This is a defeated angel, with no power to bring salvation. This is an angel from a world that has lost God and those who would do His will. In another angel sculpture (or perhaps a “sand fowl”), also a body on three stick legs – only one serrated wing remains, his torn body gapes, revealing his innards of scrap metal (akin to the sculpture “Nest” by Yechiel Shemi). Look at “Satan and the Angel” facing each other - two angels of death: a pair of torn corpses; one holding a spear, the head like a skull; the other with a spread serrated wing. They are elevated on a pole, and are constructed of iron scaffolding rods that expose their yawning open bellies.

In Tumarkin’s early mythology there is no difference between angels, animals, and humans. Thus, this figure that holds a long stick, may represent an animal, or maybe a human, a twisted, ugly entity, with warts, amputated limbs, the repulsive remains of a life of punishment. The figure is raised on a short pipe above a stage/platform (a disc and a winch welded together) and is supported by the long, narrow rod she is holding. Is she a warrior of some sort with a spear, a warrior that is also a victim? No trace of spirituality in that figure - just rotten flesh, and nothing more. Perhaps hunter and prey? Whether one or the other, both are masses of torn flesh, empty, charred, defective, limbless. The victor is as defeated as the victim. Once more, in Tumarkin’s early work, existence is brutal, repelling any spark of sublime humanity. In the same connection, another work represents a torn body balanced on a tall, slender pillar. Decomposition and decay have eaten away the body, which has lost all human or animal likeness, so that only a wild vegetable growth remains.

The “Lizard” conforms to the creeping debasement seen in some of the early animal sculptures (and to the fallen bodies). It stretches in a low, fine horizontal line, (more than a little like Giacometti’s work) and its shape resembles that of the iron cat that Tumarkin made in 1957, now in the collection of Ami Braun. The Lizard has two hollow, ball-like eyes in its round head (Rudi Lehman to Tumarkin: “Never make a figure without eyes.”); long neck, long tail, at either end of a long, rough body with a large, gaping hole at the rear end. Compare it with another sculpture in this group - “Reptile with Branch”, creature or branch, its body is rife with bulges and prickles. Anti-aesthetic, violent, it is a pre-historic presence, primeval, the antithesis of “culture.” Compare it too with the Crawling Corpse. The carcass lies before us; projections, “thorns”, short spikes at the end of the tail, on the legs, round the large head and mouth, all from scrap metal; destruction, death, violence, danger - a dreadful world.

The bird, possibly an owl, another in Tumarkin’s early series of owls, is poised, cone-shaped, on legs. One end of the body (Q. tail?) is sharp, jagged and thorny, gaping. The other end (Q. head?) is rounded, with a lidded opening in the cone, which is perforated by a large “eye”. It rests on round gear-wheels, and this damaged entity is roughly welded together. The body is hollow. The head is partly open. One side of the body is torn and reveals unfriendly “organs” of scrap. These qualities also feature in the body of the iron “Insect” that Tumarkin made in 1975, also in the Ami Braun Collection. (For some reason, in the catalogue of the Collection from 2009, the sculpture is called “Prometheus”). Its spool body is torn, exposing “organs” of junk metal, from which emerge rods and nails representing legs, antennae and so forth.

Even the likeable Cat is caught, not for his own good, in this early existence of Tumarkin, even he is condemned to an aggressive-regressive existence. The body is a sheet of iron, supported on four very short, almost non-existent legs. The sheet of iron has an aggregation of sharp, triangular iron pieces welded together, from which the head of the cat (he too consists mainly of a heap of welded triangles, except for the eyes - two welded rings of scrap) emerges. Beside the body is the tail - a rod covered with prickly globules. The welded triangles, etc., leave open spaces, “aerating” the structure, which has apparently been damaged by both erosion and corrosion, if not by something worse.

So here are 31 rare sculptures, grouped together for the first time. Fifteen of them are more familiar to us from books and exhibitions. They are the fertile ground on which Yigal Tumarkin would create new works in the mid-60s and later. They are the basis for future sculptures that will grow in size and be exposed to the New York (pop-art) scene; that will also open a dialogue with Christian and Renaissance art, and will bewilder us with their socio-political protest, by crushing armaments into sculptures (“swords into ploughshares”/r.m.). Everything began here, in Amsterdam and Paris, in the 50 or more sculptures made during two years, originating out of avant-garde input, multi-directional, as described above. Above all, they are deeply rooted in Existentialism, constituting an entrance to the spiritual world of Yigal Tumarkin, a world of victims dripping with blood, a world of black sunlight, a suffering world that says yes to myth, and no to religion, a world in which, amazingly, the banner of Humanism waves over the corpses of mankind.