Action. Photography | צילום. פעולה 10/06/2011 - 21/06/2011

Action. Photography

In recent years, following the digital revolution and the technological innovations that have simplified the use of cameras and made them widely accessible, while facilitating the creation of high-quality images, the status of photography as an artistic medium is being rethought. The sense that photography has exhausted its potential as an art form, and the growing awareness of the limitations of this medium, parallel to "the return of painting," have led photographers to search for new forms of artistic expression, and to engage in a dialogue with a range of different mediums – including painting (one early example of this trend is Wolfgang Tillmans' series of abstract photographs of colored brushstrokes on photographic paper, for which he won the Turner Prize in 2000).

The long-standing and complex relationship between photography and painting has been extensively written about by art scholars and theorists. One central contribution to this discourse was Peter Galassi's 1981 exhibition catalogue Before Photography; Painting and the Invention of Photography, which examined the influence of photography – the art world's step-child – on painting. The current exhibition, "Action. Photography," offers a contemporary gaze at the relationship between photography and painting from an inverse perspective; it examines the invasion of painting on photography, as well as painting's actual intrusion into the photographic medium. The photographs and video works featured in this exhibition do not allude to the history of art or turn to it for inspiration (as is the case, for instance, in the works of Ori Gersht, or in Thomas Struth and Andreas Gursky's photographs of paintings in museum spaces), but rather build directly on the act of painting. Some of the artists, such as Ronnie Setter and Eli Aharoni, introduce traditional artmaking techniques such as etching or printmaking into the photographs. The works of other artists, meanwhile, evolve out of paintings: Tomer Kep's abstract paintings serve as the backdrop for his photographs, while Boaz Aharonovitch deconstructs and reconstructs compositions by Jackson Pollock. In Aharonovotich's works, as in the works of Dror Daum and Michel Platnic, the introduction of painting into the photographs gives rise to a theoretical discourse on the relations between painting, photography, and additional mediums. In other works (by Tomer Kep, Roger Ballen, and Boaz Aharonovitch), painting serves as a means for psychological expression, infuses the photograph with additional emotional registers, or alludes to concealed themes.

Ronnie Setter's manipulated photographs, which are mounted on light boxes, build on historical images of Berlin during the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), which were chosen and acquired from the Bundesarchive (the German federal archive). This series features sites related to Alfred Döblin's 1929 novel Berlin Alexanderplatz, which contained premonitions of the Nazi rise to power. These historical photographs, which capture a specific time and place, are printed on transparencies, onto which the artist subsequently etched drawings of her own using a screwdriver. The archival photographs are all black-and-white; the chromatic effects in the works are a result of the lines etched into their surface, and of the light passing through them. As the etching marks grow deeper, effacing and attacking the photographs, the palette of each image grows lighter, and the etchings seem to overtake the photographs – as if Berlin on the eve of the Nazi accession to power were the arena for a struggle between the two mediums (it is worth noting the violent connotations of at least some of the sites depicted in the photographs – the Moabit prison and the security system at a busy train station. Eli Aharoni's photographs similarly combine techniques borrowed from the worlds of painting, printmaking, and etching. The images she chooses, which often feature animals, have a nostalgic or naïve character, and are characterized by simple subject matter and compositions – images of rural landscapes, farm animals such as ducks or donkeys, and lovable wild animals such as fawns. The complexity of the resulting images is due to the introduction of painterly action into the photographs; this tactic endows the images with an ambiguous, multilayered appearance, whose (painterly) origin is not always clear.

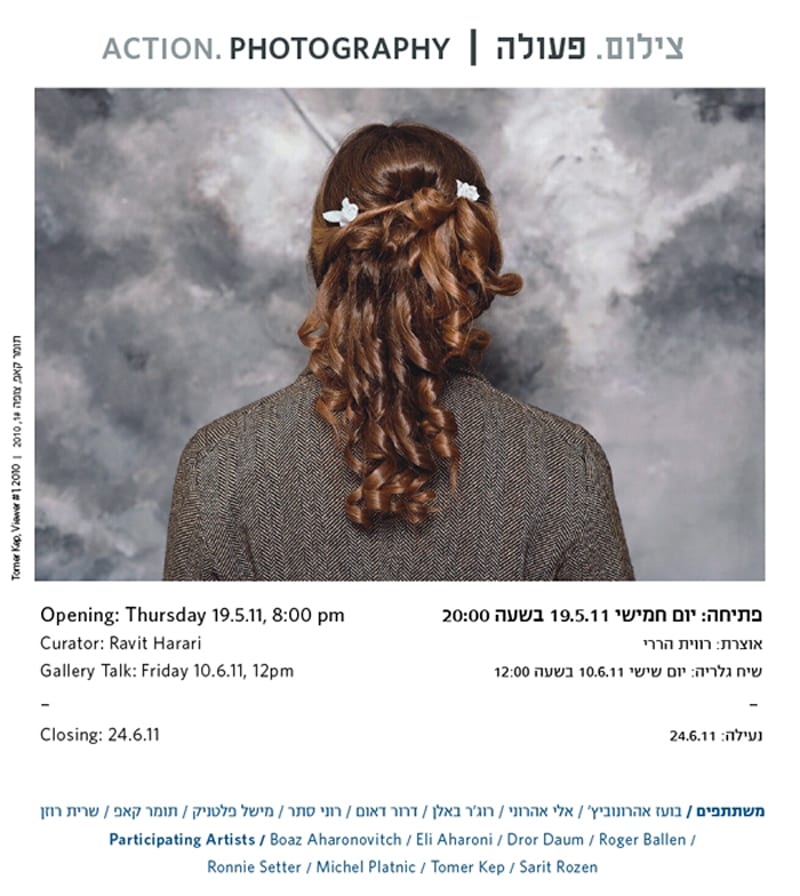

Tomer Kep's abstract watercolors or acrylic paintings, which are artworks in their own right, are integrated into his photographs as an enigmatic background, replacing the back wall of the photographic set and raising questions concerning the nature of the photographed site. Kep's photographs have an intentionally nostalgic, old-fashioned character. The domestic spaces he photographs appear to be suffused with personal and familial memories, which are alluded to by traces of his parents' presence – a photographed drawing of his mother, or a passport photograph of his father as a young man. The painted background, which at times resembles a stormy sky, infuses the painting with a somewhat meditative quality that seems to sever the scenes of the domestic space in which they were photographed, endowing them with the appearance of a dream that cannot be related to a specific time or place. A similarly surreal quality infuses the photographs by Roger Ballen, which capture a series of enigmatic paintings and wall drawings. These images raise questions concerning the site in which they were photographed, which appears at once as a concrete place and as an emotional space. Ballen has long been documenting life on the margins of South-African society. The works featured in this exhibition, which are all part of the series "Boarding House," focus on sculptural and linear elements in abandoned houses in Johannesburg's impoverished neighborhoods. This series was photographed in a squat temporarily inhabited by various homeless people. This strange, crowded space is filled with broken furniture, junk, and debris that attests to the lives lived in this place. The walls are covered with expressive drawings that resemble simple yet dark children's drawings, infused with agitated, restless, uncontrollable brushstrokes. In the context of the difficult living conditions in which they appear, these murals are reminiscent of cave paintings that invite the viewer to embark on a journey to the dark and primitive side of the human soul and of human existence.

The mural featured in Ilit Azoulay's photographs is remarkably subtle. Azoulay, whose works often capture sites slated for destructions, used the wall in this case as a support for the creation of new sites. This wall does not serve as a background, but rather as a support imbued with numerous secrets and messages. Like the walls in Ballen's works, her wall is charged with memories and signs of life, yet it does not create a protective environment. She builds up the wall in these works layer by layer, as if priming a canvas in preparation for a painting. Building on the bits of paint and cracks in an old wall, she adds her own marks and strokes of color, which come together to create a panoramic painting of an imaginary landscape – a combination of a barren terrain and a pastoral scene reminiscent of a sunset.

The title of Dror Daum's photograph D.O.A. alludes to the medical expression "dead on arrival." This photograph features a wastepaper basket filled with crumpled drawings of butterflies that resemble the pages of a manuscript thrown out by a frustrated writer, thus transforming the bin into a butterfly trap. These butterfly drawings are "dead" both metaphorically and in terms of the medium in which they captured: these images, which originally appeared in color in a Hungarian botanical book from the 1950s, were Xeroxed, stripped of their material qualities, and then photographed again with a camera.

The pair of objects in Boaz Aharonovitch's series In Treatment underwent a similar process: two drawings (or rather, nervous doodles) created by the artist on two sheets of paper were crumpled and sculpted into miniature objects, whose careful formation stands out in contrast to the instinctively created doodles. These objects were photographed and then meticulously processed, enlarged, and printed to produce highly aesthetic, glorified images of the crumpled notes, lending them the appearance of sparkling "diamonds" against a bright white background. Here too, the agitated doodles offer a photographic testimony of a specific psychological or emotional state (they were drawn in the process of therapy); as such, they acquire a symbolic role as images of the psyche. In another pair of photographs, Aharonovitch performed an action that relates directly to the dialogue between painting and photography. He photographed sections of several paintings by Jackson Pollock, disassembled the photographs into individual brushstrokes and drips, and then painstakingly created "new" Pollock paintings that do not exist in reality. Yet whereas Pollock attempted to distance himself from the direct representation of reality, and to disassemble his image into fragments, Aharnovitch attempts to reconstitute the fragments into a new whole. Pollock's "action painting" was concerned with the process of painting itself – an unplanned and spontaneous process accompanied by dramatic bodily gestures; in Aharonovitch's work, meanwhile, the process of "action painting" is replaced by a carefully planned and calculated form of "action photography," which takes place on the computer screen rather than on an empty canvas.

Michel Platnic's work similarly engages in a direct dialogue between different mediums. Painting, photography, video, and performance all come together in his two portraits of King Charles II and Queen Victoria. A copy of the original painting created by Platnic serves as the background for a photographed performance, in which actors replace the painted figures. Their painted bodies blend into the composition in the background, as they seemingly reenact the manner in which the royal figures faced the painter charged with commemorating them in the pre-photographic age. Here too, the body serves as a tool for the creation of a painting. In this case, however, the dramatic bodily gestures associated with action painting are replaced by a concerted effort to preserve the body's static pose. The result is a video that appears at once as a motionless photograph and as a painting gone awry, in which only the figure's eye movements and breathing reveal the manner in which it was created.

Ravit Harari